The process of creating a new costume for myself always begins with my personal connection to that costume and my reasons for wanting to invest so much time into making it. My motivation is purely personal. Each costume I have built for myself, which is now featured on my website, started with a desire to have that costume for me. For example, the latest batch of Jabba costumes stems from my childhood love for those characters; I always enjoyed them but felt it was significant work to bring them to life.

The costume-making process is actually quite lengthy and starts with extensive research. It is easy to overlook details during the preliminary research phase, so I dig for images from as many angles as possible and from as close as possible. My philosophy revolves around screen accuracy, which means some details may not be visible on screen. Sometimes, I have to make educated guesses or executive decisions based on my extensive experience in costume creation and the creative field. I try to empathize with someone under pressure to create something visually appealing that will only be seen for a few seconds on screen.

The first step is conducting this preliminary research and gathering as much data and reference material as possible. The second step is sketching. I sketch what I can see, what I can’t see, and how I expect the costume to look. It’s crucial to approach this with the understanding that the costume will not only be seen on screen for a few minutes but also worn for hours. Therefore, I have to consider how the clothing will be worn, not just how it looks.

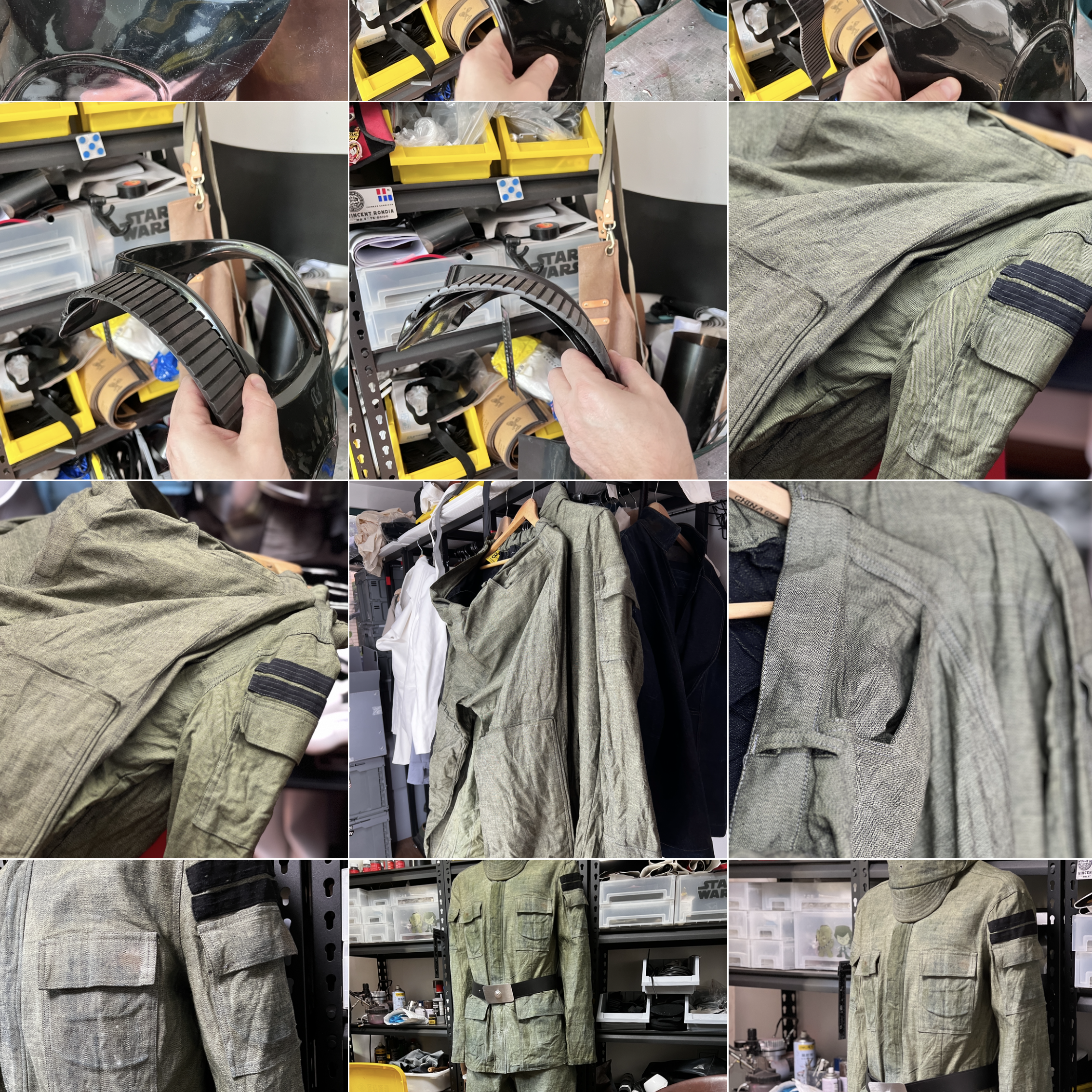

Next, I source the initial materials based on my gathered information. Often, I know exactly what fabric is needed, but sometimes I don’t. Other times, I might find that what exists in various markets doesn’t match my requirements, or the fabric may have been made specifically for that purpose. To bring the costume to life, I either need to find something very close or have it custom-made.

Once I have sourced all the materials, I begin the making process, which starts with a prototype. This prototype does not need to be made from the final fabric; it just needs to be made from any available material. The goal is to check the design, the curtain pattern, and the fit to see if the ideas actually work. Adjustments are often necessary because what appears to work in sketches may not function well when worn.

Once we are reasonably satisfied with the first prototype, we create a second version using the materials we have sourced. This version lets us see an almost finished product and check the fabric’s appearance. Different fabrics may look different when sampled compared to when they are made into full clothing. Colors can shift slightly, and the fabric’s weight can alter the final product’s visual feel. This prototype also enables us to start showing it to the world, allowing us to gather feedback—both positive and negative—that helps us refine our approach before moving to the final production version of the costume.

This entire process can take up to a year and requires a significant investment of time and money for materials, prototypes, and so forth. However, it doesn’t mean the work is complete once the first production version is released. There may be ongoing adjustments needed as new information becomes available or if the Costume Reference Library (CRL) is updated. In those cases, we need to revise our patterns. Fortunately, these updates are typically faster because we’re dealing with smaller details, allowing us to adapt an existing pattern rather than create a completely new one. Sometimes, this process also requires sourcing new materials to meet updated requirements.